I came across something moderately fascinating yesterday in the journal of Neurology in Clinical Practice in Iowa (the may 1983 issue), which touches on many issues that interest me; allow me relate it you below:

There was a university hospital in the city of Ghent which specialized in patients with damaged visual systems; a lot of people who had lost their visual memory due to various unfortunate accidents and the like.

But there was a rather singular case involving a young girl who, while not blind, didn’t seem to have direct access to her visual memory. When the researchers first had her admitted to the hospital, they carried out a simple test: they brought her into a room containing several objects placed at various points, and asked her to describe what was in the room.

Now it is very common for children, when talking of the position of various things, to describe them relative to their own position, but this girl seemed to first talk of a blue cube as being in the corner, then of a toy horse as being above the cube on a shelf, and of the lamp being in the other corner left of the horse and so on. Also, curiously, she mentioned that she was in the room.

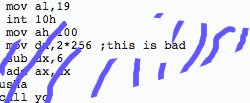

They then wanted to perform a bunch of other tests involving asking her to describe what she saw when presented with various pictures, but they fell apart: she was unable to understand the content of pictures or photographs except with the greatest of efforts on her part and of exhaustive explanations on the part of the researchers that would rather have invalidated the tests anyway.

They tried, for instance, to explain to her that if something in a picture appears to be small, then it is far away. She was completely unable to grasp this; she said that whether something was far away or near by it was still the same size, that things didn’t just get smaller when they were moved far away. And the doctors said “yes, but they *look* smaller”. She was vehement that they didn’t, however.

Another day, they presented her with a mirror and asked her to describe what she saw in it; she indicated that she saw nothing “in” it but could see herself a lot better now.

Anyway, on the basis of these curious results, and a few other tests, and a mathematically-literate psyche nurse, they ended up conjecturing that her visual system was exceptionally well-developed, to the extent that she no longer needed to access directly information from her visual system, that rather she only had access to a definite 3D model constructed inside of her brain, without a fixed centre on herself necessarily, or without having to deal with 2-dimensional projections like the rest of us (This also made her a rather slow learner when it came to reading).